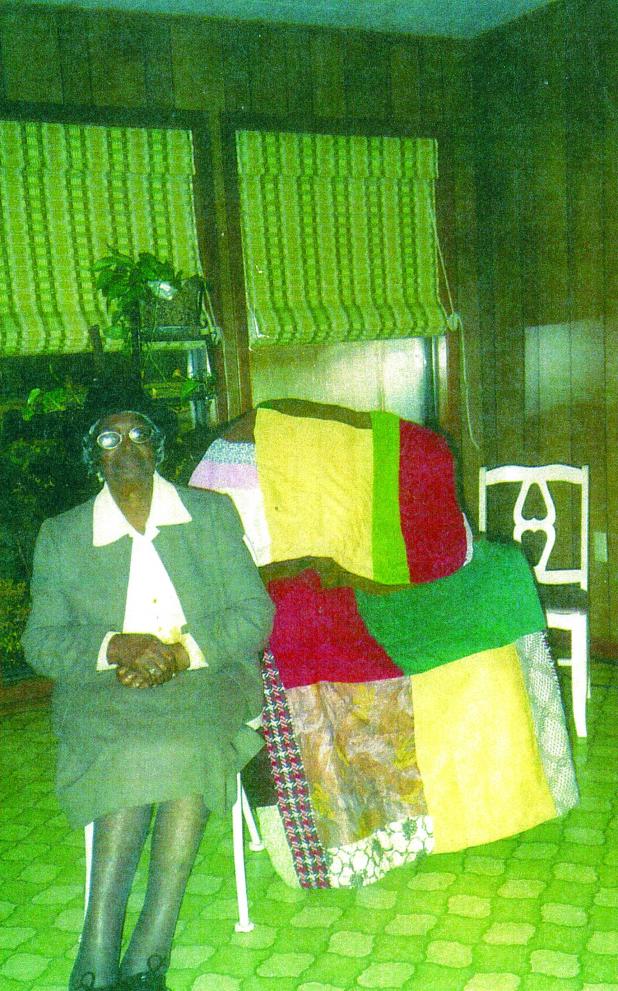

Lucille Stewart

Scrapping cotton for quilts remembered

Life was extremely hard for sharecroppers living on plantations in the South.

Women toiled in the cotton fields with their husbands and children, then took care of their families. At night, after a long day of work, the women quilted. It was their responsibility to provide covers to keep the family warm in homes that were poorly insulated.

My grandparents, John Henry and Susie Cooper Lewis, were sharecroppers in North Louisiana at the turn of the 20th century. They lived on Dr. Shepherd’s plantation in Mangham in the Delta where “cotton was king.” My grandparents had 11 children. My mother, Lucille (“Cill”) Lewis, was their youngest girl. She worked closely with her mother -- known as “Big Mama” to all of us grandchildren.

As the winter months approached, Big Mama would begin making quilts for her family and would ask Dr. Shepherd if she and my mother could scrap cotton.

“Scrapping” cotton meant gathering the cotton left by pickers after a harvest. This scrap cotton, which could not be picked due to standing water, was oftentimes scattered all over the cottonfield. Dr. Shepherd gave his permission because he knew the family would need the cotton for quilts.

After scrapping the cotton, my mother and grandmother would take a hickory switch and beat the seeds out of the cotton before using it to layer between the top and back of their quilts.

Big Mama’s quilts were made from pieces of clothing worn by family members, scraps of cloth given to her and decorative fabric from cornmeal and seed sacks. My grandmother’s quilts were not fancy, but simply fabric cut in large pieces and sewn together. When her quilts became too old to use as covers, they became insulation.

During quilting season, Big Mama invited other women to come to her house and help her quilt. The women looked forward to tea cakes and other desserts.

Through songs, prayers, and testimonies, they held a kind of church service, crying and shouting as they listened and fellowshipped, telling of the goodness of God. The quilting circle went from house to house, making sure each family on the Shepherd plantation had quilts for the harsh winter.

My mother married my father, Rev. James H. Stewart, and they migrated to Rayville -- about 20 miles from Mangham -- where they reared their seven children.

Mama used the quilting skills she learned from Big Mama to provide warmth for her own family. She made plain utility quilts from our family’s clothing just as her mother had. She quilted on the bed using four smoothing irons to hold the quilt in place. Although Mama didn’t scrap cotton anymore, she used old blankets and cotton she got from friends in the country to layer into her quilts.

I remember my mother quilting while she helped my siblings and me with our homework, calling out spelling words and listening to us read. She could often be heard joyfully singing as she quilted. My brothers, sisters and I are thankful for the quilting tradition passed down from Big Mama to our mother. I am blessed to have two of the quilts my mother made, and I have bought other quilts because of my love for the art of quilting and the stories each one tells.